LAIKA'S CISCO NOTES MASTERDOC

for future reference by me for me

lesson 3

lesson 4

lesson 5

lesson 6

lesson 7

lesson 8

lesson 9

lesson 10

lesson 11

lesson 3

network protocol overview

network communications protocol

allows two or more devices to communicate over one or more networks.

examples include ip, tcp, http

network security protocols

secures data to provide authentication, integrity, and encryption

examples include ssh, ssl, tsl

routing protocols

allows routers to exchange route information, compare it, and select the quickest option availible

examples include ospf, bgp

service discovery protocol

used for the automatic detection of devices or services

examples include dhcp, dns

general terms

network protocol suite

a group of inter related protocols necessary to perform a communication function

open standard protocol suite

freely available, can be used by any vendor on their hardware

standards based protocol suite

endorsed by the networking industry, and approved by a standards organization. insures that products from different origin can interoperate

tcp/ip layers

4 - application: represents data to users, plus encoding and dialog control

3 - transport: supports communication between various devices across diverse networks

2 - internet: determines the best path through the network

1 - network access: controls the hardware devices and media that make up the network

tcp/ip layers examples

(// means subcategory, //// means item in said subcategory)

application layer

// name system

////DNS [domain name system]

*

// host config

//// dhcpv4

//// dhcpv6

//// slaac

*

//// smtp

//// pop3

//// imap

*

// file transfer

//// ftp [file transfer protocol]

//// sftp

//// tftp

*

// web and web service

//// http

//// https

//// rest

transport layer

// connection

//// tcp

*

// connectionless

//// udp

internet layer

// internet protocol

//// ipv4

//// ipv6

//// nat

*

// messaging

//// icmpv4

//// icmpv6

//// icmpv6 nd

*

// routing protocols

//// ospf

//// eigrp

//// bgp

network access layer

// address resolution

//// arp

*

// data link protocols

//// ethernet

//// wlan

application -> transport -> internet -> network access

content layer -> rules layer -> physical layer

computer receiving: ethernet -> ip -> tcp -> data

computer encapsulating: data -> tcp -> ip -> ethernet

osi model layers

7 - application: contains protocols used for process-to-process communications

6 - presentation: provides representaions of data being transferred between the application layer

5 - session: provides services to the presentation layer to organize its data exchange

4 - transport: defines services to segment, transfer, and reassemble data between end devices

3 - network: exchanges individual pieces of data over the network between end devices

2 - data link: describes methods for exchanging data frames between devices over a common media

1 - physical: decribes the mechanical, electrical, functional, and procedural means to activate, maintain, and de-activate physical connections for a bit transmission to and from a network device

ip addresses

there are two parts to an ip address: the network and host portion

network portion[prefix]: the left most part of the address. indicates what network the device is on. all devices on the same network have the same network portion,

host portion[interface id]: remaining part of the address. identifies a specific device on the network. this portion is unique to each device.

example: 123.456.7.890

123.456.7. is the network portion

890 is the host portion

subnet mask divides the 2

mac versus ip

mac: identifies devices locally

ip: identifies devices globally

enable secret: gives extra security to enable password

enable password: priv exec mode, global ect

lesson 4: physical layer

the physical layer sits at the bottom of the osi stack, and is the primary foundation of the network.

4.1 == purpose of the physical layer

describes the purpose and functions of the physical layer in the network!!

// 4.1.1 == the physical connection

a physical connection can be wired or wireless using radiowaves!! very cool

while wired connections are connected with real cables, devices on a wireless network must be connected to a wireless AP [access point] or router

NICs [network interface cards [a physical chip in the device]] connect a device to the network. ethernet NICs are used for wired connections, and wlan NICs are used for wireless. an end device may have one or both of these.

// 4.1.2 == the physical layer

the osi physical layer allows the bits that make up the data link layer frame to be transported across the network media [wires or air]

this layer takes a complete frame from the data link layer and encodes it as a series [not all at once!!] of signals that are sent to the local media [wires or air]

PDU: protocol data unit; a basic unit of communication between devices, holds all those headers. ex, frames, packets

// frames vs packets vs segments

segments: split up data; the first step of packaging

packets: add addresses for routing; the second step

frames: prepare data for physical transmission; the final step

4.2 == physical layer characteristics

describes characteristics of the physical layer woah

// 4.2.1 == physical layer standards

the physical layer consists of electronic circuits, media [wires and air], and connectors. all of these components must met certain standards.

// 4.2.2 == physical components

the physical layer standards address physical components, encoding, and signalling

physical components are the electronic hardware, media [wires or air], and other connectors that send bit-representing signals

components like nics, interfaces, connectors, cable materials, and cable designs all must meet these standards

// 4.2.3 == encoding

encoding [or line encoding] is a method of converting data bits into a predefined 'code'. these codes are groups of bits used to make a predictable pattern that can be read by both the sending device and the recieving device

simply, its a method used to represent digital information, like how variables represent data in javascript [to natalia: i know you dont know javascript so this will go right over your head lolol]

ex. manchester encoding [used by older ethernet standards] == high to low voltage equals a 0, while low to high equals a 1

// 4.2.4 == signaling

the physical layer has to make the signals [electrical, optical, wireless] that represent the 1/0 binary on the media [wires or air]

the way that the bits are represented is called the signaling method. the layer's standards must tell what kind of signal means a 1 and what means a 0. think morse code

// 4.2.5 == bandwidth

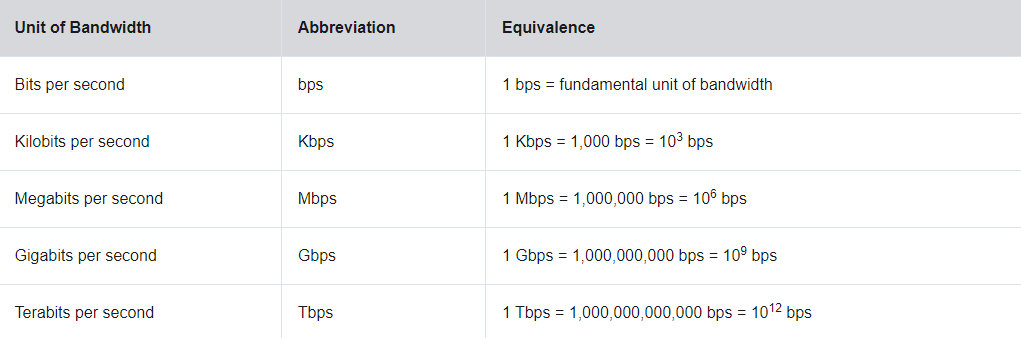

data transfer is mostly discussed in terms of bandwidth

bandwidth is the capacity at which a medium can carry data [simply how mush data from a can get to b in a certain amount of time]

typically measured in kbps, mbps, or gbps. remember, the 'b' stands for bits, not bytes

a single bit is a boolean value [0/1]. a byte is 8 bits.

what can determine the bandwidth of a network you may ask?

* properties of the physical media [the connection [wires or air]]

* the systems that signal and detect network signals

* the law of physics

// 4.2.6 == bandwidth technology

what measures good bandwidth? latency, thoughtput, and goodput of course!!!!!!!

latency means the amount of time [+ delays] that it takes for data to travel from a to b

thoughtput means the number of bits transferred over a given period of time

* thoughtput can be pretty fast, but never faster than the slowest link in the transfer path

however, due to a few factors, thoughtput mostly never matches the specified bandwidth given. its usually lower than bandwidth sadly

* amount of traffic, type of traffic, latency [wait time] created by amount of devices between a and b

goodput means the amount of usable data transferred over a certain amount of time

it's pretty much thoughtput minus the traffic of many steps like encapsulation and transmitted bits

from highest to lowest, [bandwidth] > [thoughtput] > [goodput]

4.3 == copper cabling

cabling of the copper ooh

// 4.3.1 == characteristics of copper cabling

copper cables are the most common network cable. they are cheap, easy to install, and have low resistance to electrical currents

however, it is limited by distance and signal interference

data is transmitted through these cables as electrical pulses. a detector [in the network interface] of a destionation device has to recieve a signal that can be decoded to match the sent signal

however, the farther the signal travels, the more it deteriorates. [this is called signal attenuation]

because of this, all copper wiring must follow strict distance limitations

interference in timing and voltage values is also possible from two other sources:

* electromagnetic interference [EMI]: can distort and corrupt the data signals being sent due to radio waves and electromagnetic devices, such as lights or motors

* radio frequency interference [RFI]: same as emi

* crosstalk: a disturbance caused by the electric or magnetic fields of data on one wire to an ajacent wire. in telephone circuits, if this happens, you can hear the other signal's conversation. when a current flows through the wire, it creates a small circular magnetic field around itself, which can be picked up by other wires

* to counter emi and rfi, some kinds of wires are wrapped in a metallic shielding and need to be grounded

* to counter crosstalk, some kinds of wires have opposing circuit wire pairs twisted together, which prevents the crosstalk

you can also decrease the risk of electric noise by choosing the right cable type, designing the cable infrastructure to avoid known interference in a building's structure, and using the right cabling techniques such as correct handling and termination

// 4.3.2 == types of copper cabling

there are 3 kinds of copper cabling!!!!!!!!!

// 4.3.3 == unshielded twisted-pair [UTP]

utp is the most common networking media!

utp, terminated with rj-45 connectors, is used for interconnecting network hosts with devices like switches and routers

termination: connecting the cable to a device

in lans, utp cables have 4 pairs of color-coded wires that are twisted together and encased in a flexible plastic sheath that protects from damage a little bit. [the wire twisting helps protect against crosstalk]

the color coding identifies the individual pairs and wires and helps with termination

// 4.3.4 == shielded twisted-pair [STP]

stp provide better noise protection than the above utp. however, stp is much more pricy and harder to install

like utp, stp also use rj-45 connectors

stp combine the shielding techniques to counter emi and rfi, and have wiretwisting to fight against crosstalk

shielding: the shit on the outside of the cable

to use the shielding to its full extent, stp cables are terminated with special shielded stp data connectors

if the cable isnt grounded properly, the shield might make like an antenna and pickup unwanted signals

// 4.3.5 == coaxial cable

nicknamed coax, this cable gets its name from its two connectors that share the same axis

they consist of the following:

* a copper conductor where the signals flow [the main cabling in the center]

* a layer of flexible plastic insulation that goes around the copper conductor

* the insulation is surrounded by a woven copper braid, or a metallic foil, that acts as the second wire in the ciruit or as a shield for the conductor

* a cable jacket to protect a bit against physical damage

theres lots of different kinds of connectors used with coax cables; bnc, n type, and f type for example

while utp has replaced coax in most situations, coax is still used in wireless and cable internet installations

4.4 == utp cabling

more unshielded twisted pair cables!!! couldnt be happier

// 4.4.1 == properties of utp cabling

utp does not use shielding to prevent crosstalk, but it does use 2 other methods:

* cancellation: wires are paired while in a circuit, which causes their magnetic fields to oppose eachothers chargewise, cancelling out crosstalk

* varying twist numbers per wire pair: the number of twists in each wire pair is varied. each colored pair is twisted a different amount of times

// 4.4.2 == utp cabling standards and connectors

utp cabling must conform to stanrdards given by the tia/eia

there are 8 different categories of copper cabling. the higher the category, the better the ability to carry higher bandwidth rates

category 5e is currently considered the minimum, whereas category 6 is the current recommended type for new installations

male components are the plugs, while female components are the sockets

// 4.4.3 == straight-through and crossover utp cables

situations may require utp cables to be wired differently. this means that the wires must be connected in different orders to different sets of pins in the rj-45

the two main cable types:

* ethernet straight-through: the most common type, is used to interconnect a host to a switch and a switch to a router

* ethernet crossover: a cable used to interconnect similar devices, like a switch to a switch or a router to a router. these are considered legacy nowadays

[* rollover cable: used to connect a cisco workstation to a router or switch]

the most common connectivity error is using one of these cables incorrectly, so device connections should always be checked

| CABLE TYPE | STANDARD | APPLICATION |

|---|---|---|

| ethernet straight-through | both ends either t568a or t568b | connects a network host to a network device like a switch |

| ethernet crossover | one end t568a one end t568b | connects 2 network hosts or 2 network devices |

| rollover | cisco proprietary | connects a workstation to a router via adapter |

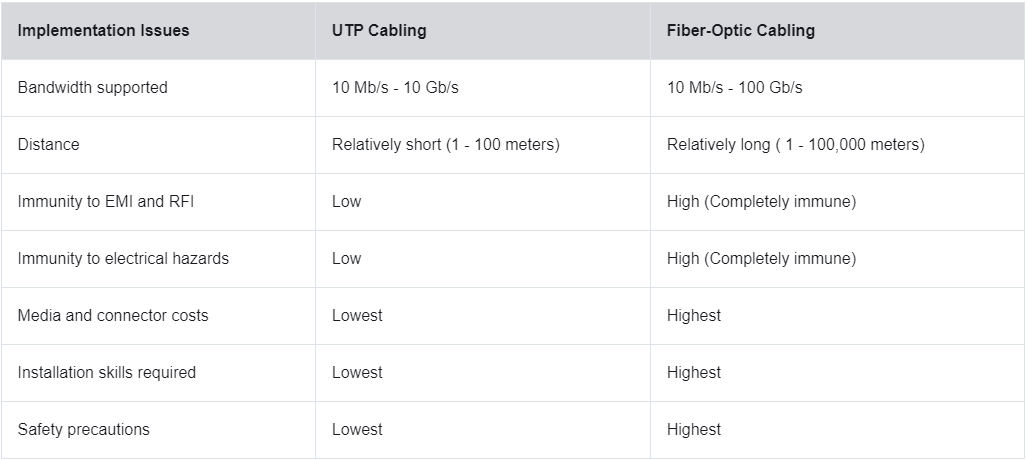

4.5 == fiber optic cabling

delicious

// 4.5.1 == properties of fiber optic cabling

is better than copper cables, but is very pricy!!

these cool wires can transmit data over longer distances and at faster bandwidth, and are immune to emi and rfi

optical fiber is actually an very very very thin piece of flexible glass, used to send bits encoded as light pulses

// 4.5.2 == types of fiber media

2 kinds!! single mode fiber [SMF] and multimode fiber [MMF]

single mode fiber produces a single straight path for the light, whereas multimode allows multiple paths for the light

however, mmf has more dispersion than smf, so it can only travel up to 500 meters before signal loss

dispersion: how far the light can spread out in the wire

// 4.5.3 == fiber optic cabling usage

fiber optic cabling is used in 4 kinds of industries!!

* enterprise networks: used for backbone cabling and interconnecting infrastructure devices

* fiber to the home [FTTH]: used for always-on broadband services to homes and small buisnesses

* long haul networks: used by service providers to connect far away places to eachother

* submarine cable networks: used for high speed, high capacity connections capable of surviving underwater

// 4.5.4 == fiber optic connectors

a connector terminates the end of a fiber optic. there's many kinds avaliable, but the only differences are size and wiring

some kinds include:

* straight tip [st]: twist on / twist off type locking

* subscriber connector [sc]: also called square connectors. uses push pull locking

* lucent connector [lc] simplex: smaller sc connector. also called little or local connectors

* duplex multimode lc: a duplex version of an lc

// 4.5.5 == fiber patch cords

fiber patch cords are required for interconnecting infrastructure devices

yellow cord means it's a single mode, and orange/aqua mean it's a multimode

// 4.5.6 == fiber versus copper

fiber is primarily used as a backbone for high traffic, point to point connections. it is also used for interconnection of buildings in multi-building campuses

4.6 == wireless media

// 4.6.1 == properties of wireless media

wireless media carries electromagentic signals that represent bits using radio or micro waves

wireless media provides the best mobility out of all media!!

however limitations are present;

* coverage area: building materials and terrain [like mountains] can limit coverage

* interference: wireless media can be easily disrupted by common devices, like cordless phones

* security: any knowledgeable unauthorized user can gain access to any transmission made [hackermode!!!]

* shared medium: wlans [wi-fis] operate in half duplex, meaning only one device can send or receive at a time. many users using the wlan may experience slower bandwidth

// 4.6.2 == types of wireless media

wireless standards set by the ieee include:

* wifi [ieee 802.11]: uses a condition based protocol called 'carrier sense multiple access / collision avoidance' [CSMA/CA], meaning that if one nic is transmitting, other nics must wait until it is finished.

* bluetooth [ieee 802.15]: aka a wireless personal area network [WPAN]. range from 1-100 meters

* wimax [ieee 802.16]: stands for mr worldwide interoperability for microwave access. uses point to multipoint topology to provide broadband access

* zigbee [ieee 802.15.4]: used for low data rate and low power communications. used for things that need short range, low data and long battery life [my nokia phone versus like an iphone 18]

// 4.6.3 == wireless lan

wlan requires 2 network devices [another list!!! ohemgee]

* wireless access point [ap not wap sadly thad be really funnie]: concentrates wireless signals and connects to copper-based network infrastructure. integrates the function of a router, switch, and ap into a single fingle

* wireless nic adapters: provides wireless communication capability to network hosts

lesson 5: number systems

we will be learning about binary and hexidecimals here!!!

5.1 == binary number system

// 5.1.1 == binary and ipv4 addresses

ipv4 addresses are shown in binary

most network administrators convert these to decimal, because it is easier to read

addresses contain a string of 32 bits, devided into 4 sections called octets. each octet contains a byte seperated with a dot

// 5.1.2 == video yurrr

decimal is base 10, while binary is base 2

decimal ex.: 10, 100, 1000

binary ex.: 1, 2, 4, 8, 16

ip address octets represent the amount of a power of 2 between 0 and 7, starting at 7. they are all added together, making that octet

to make binary from a decimal, starting at 128, go down the list and subtract and count up the number of subtractions

7-0: 128, 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

// 5.1.3 == binary positional notation

big phat example

| position value | 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| binary number [11000000] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| add em up... | 128 | +64 | +0 | +0 | +0 | +0 | +0 | +0 |

| reslut | 192 |

5.2 == hexadecimal number system

// 5.2.1 == hexadecimal and ipv6 addresses

while ipv4 addresses use binary, v6 and ethernet mac use hexidecimal.

hexadecimal uses a base 16 system. this uses the digits 0-9 and letters a-f.

| decimal | binary | hexadecimal |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0000 | 0 |

| 1 | 0001 | 1 |

| 2 | 0010 | 2 |

| 3 | 0011 | 3 |

| 4 | 0100 | 4 |

| 5 | 0101 | 5 |

| 6 | 0110 | 6 |

| 7 | 0111 | 7 |

| 8 | 1000 | 8 |

| 9 | 1001 | 9 |

| 10 | 1010 | a |

| 11 | 1011 | b |

| 12 | 1100 | c |

| 13 | 1101 | d |

| 14 | 1110 | e |

| 15 | 1111 | f |

these addresses are 128 bits, and each 4 bits is represented by one hexadecimal digit. this totals 32 hexadecimal digits.

also not case sensitive!!

ipv6 addresses are formatted with a ':' between each 4 digits. a hextet means 4 hexadecimal values.

// 5.2.3 == decimal to hexadecimal

* first, convert the decimal number to 8 bit binary strings

* divide the strings into groups of 4 from the right

* convert each of the 4 binary digits into hexadecimal

ex with the number 168

** 168 in binary is 10101000

** 10101000 can be split into 1010 1000

** 1010 is a and 1000 is 8

** answer: a8!!

// 5.2.4 == hexadecimal to decimal

do the above backwards!!! hex -> binary -> decimal

lesson 6: the data link layer

6.1 == the purpose of the data link layer

// 6.1.1 == the data link layer

the data link layer prepares network data for the physical network in the physical layer!

this layer is responsible for nic to nic communications.

[remember: nic stands for network interface card!!]

the data layer link does all of the following:

* lets upper layers access the media, because the upper layers have no clue what type of media is being used

* accepts layer 3 packets [ipv4 or v6] and encapsulates them into layer 2 frames

* controls how data is sent and received over the media

* exchanges frames with endpoints over the network

* recieved encapsulated data [usually layer 3 packets] and sends them to the proper upper-layer protocol

* detects errors and rejects corrupt frames

nodes: devices that can get, make, store, or send data along a communications path.

these can be end devices [ex. laptop] or an intermediary device [switch].

with no data link layer, network layer protocols like ip would have to adapt to each kind of media connected.

// 6.1.2 == ieee 802 lan/man sata link sublayers

what the fuck does that mean

these standards are specific to ethernet lan, wlan, wpan, and other types of area network.

it's basically just the two halves of the data link layer.

the two sublayers are:

* logical link control [llc]: this ieee 802.2 sublayer talks with the networking software on the upper layers and the device hardware on the lower layers.

it writes information to frames that tells it what networking protocol is being used for the frame.

this lets multiple layer 3 protocols use the same network interface and media.

[in short, it takes the network protocol data, and gives it layer 2 control information to help it get to it's node.]

* media access control [mac]: implements this sublayer [ieee 802.3, .11, .15] in the hardware.

it is responsible for encapsulation and mac.

it also provides data link layer addressing and is a part of various physical layer technologies.

[in short, it controls the nic and other hardware that sends or gets data on the lan/man medium.]

but wait!! the mac layer can do so much more!!

it can do...

** frame delimiting, which provides important delimiters to identify fields within a frame. this provides synchronation between the sending and recieving nodes.

[note-- delimiters are just a character that marks the beguinning and/or end of something. like the p and /p in html.]

** addressing, which just gives a frame source and destination addresses for sending the layer 2 frame between devices.

** error detection, which includes a trailer used to detect transmission errors.

[note-- trailers are control information sent at the end of a data transmission.]

the mac sublayer also provides media access control [also called mac] that lets devices communicate over a half-duplex. full-duplex do not require access control.

note-- man stands for metropolitan area network.

// 6.1.3 == providing access to media

the data link layer is responsible for controlling the transfer of frames accross media.

-- first, it accepts a frame from the medium [wires or air]

-- next, it de encapsulates the frame

-- then, it re encapsulates the packet into a new frame

-- and lastly, it forwards the new frame part that corrisponds to the segment of the physical network.

// 6.1.4 == data link layer standards

the data link protocols are usually not defined.

companies that do define the standards that apply to the network access layer include ieee, itu, iso, and ansi.

6.2 == topologies

// 6.2.1 == physical and logical topologies

2 kinds 2 kinds 2 kinds 2 kinds 2 kinds:

** physical topology: identifies physical connections [like wires] and how and how all the devices are connected. sometimes specifies rooms or locations.

** logical topology == shows how frames transfer from one node to another in a visual medium. sometimes specifies device labels and layer 3 ip addresses.

[in short: physical = what we see, logical = what the computer sees]

// 6.2.2 == wan topologies

wans are interconnected in 3 ways:

** point to point: one wan to another wan

** hub and spoke: one wan to many wans

** mesh: many wans connected to eachother

// 6.2.3 == point to point wan topologies

as said above, point to point directly connects two nodes.

however, nodes do not nessesarily have to share their media with other hosts.

in point to point protocol [ppp], a node does not have to think about where the information needs to go, because theres only one possibility.

a source [start] and destination [end] node can actually be indirectly connected over multiple intermediary devices.

what's cool is that in this situation, the logical topology does not change, because the point to point connection is still the same.

// 6.2.4 == lan topologies

in multiaccess lan, end devices are connected to eachother via star or extended star topologies

star topologies look like a *, with devices at the end of each line, but no end device in the middle. in the middle would instead be an intermediary device, like an ethernet switch.

extended star topologies look like a *-*, with 2 star topologies connected via multiple ethernet switches.

theres a couple legacy toplogies as well. these arn't frequently used anymore, but are still good to be aware of nonetheless.

** bus topologies involve all end devices chained together, and terminated at each end. this was done via coax cables.

** ring topologies involve all end devices linked together in a ring, human centipede style. this does not need to be terminated.

// 6.2.5 == half and full duplex communication

the daring duo, half duplex and full duplex!!!

** half duplex: both devices can send and receive, but not at the same time.

** full duplex: both devices can send and receive at the same time.

it is crucial that any connected devices use the same duplex mode. no mismatching!!

[ note-- ethernet use full-duplex nowadays, but wlans still use half-duplex.]

// 6.2.6 == access control methods

a multiaccess network is a network that can have 2 or more end devices accessing the network at once.

ethernet lan and wlan are examples of multiaccess networks.

some multiaccess networks require rules to decide how devices share the media.

there are 2 sets: contention based access and controlled access

** contention based access: where all nodes are half-duplex, so only one device can send at a time.

there are 2 individual methods of this, but i will get into that in 6.2.7/8. ex: wlan.

** controlled access: each node waits its turn to use the network. this is almost obsolete.

// 6.2.7 == contention based access - csma/cd

note-- csma stands for carrier sense multiple access, which is a mac protocol where a node must check and wait until the network is clear to send data.

the cd stands for collision detection! this is used to detect if 2 devices send frames at the same time over a half-duplex.

if this happens, then both of the datas sent will be corrupted and need to be resent.

when a frame is sent over this kind of access method, it will go to all other devices, but the ones that don't need the data will just ignore it.

this is used in legacy ethernet lans.

// 6.2.8 == contention based access - csma/ca

the ca stands for collision avoidance!!

sometimes the nic can't tell if the network media is in use. to prevent collisions, it will wait to transmit.

when a device transmits, it logs how much time it will take. this information is sent to all other devices on

the network so they know how long the media will be in use.

6.3 == data link frame

// 6.3.1 == the frame

what happens to the data link frame when it moves through a network? find out here!

the data link layer prepares the encapsulated data for transport by giving it a header and a trailer to make a frame.

each frame has 3 parts: header, data, trailer.

the data link protocol is in charge of nic to nic on the same network. even though there are lots of differant data link layer protocols

, all of their frames have the same 3 parts listed above. the structures of the header and trailer can vary, however.

there is no one size fits all protocol. control needs vary based on the conditions given. the header and trailer can be bigger or smaller to help combat this.

// 6.3.2 == frame fields

framing breaks the header and trailer into bite sized pieces.

some genertic frame fields include...

-- header: frame start, addressing, type, control

-- trailer: error detection, frame stop

but what do these fields mean???? fun table time!!

| frame start and stop | identifies the start and end of the frames. |

|---|---|

| addressing | tells the source and destination nodes. |

| type | identifies the layer 3 protocol in the data field. |

| control | identifies special flow control services like qos. qos gives special priorities to certain messages. |

| data | contains frame payload [packet header, segment header, data] |

| error detection | included after data. makes up the trailer. determines if the frame arrived without error. |

a sending node makes a logical summery of the contents of the frame, called the cyclic redundancy check [crc].

this value is put in a frame check sequence [fcs] field to represent the contents of the frame.

in ethernet trailers, the fcs can be used to determine if there were any transmission errors.

// 6.3.3 == layer 2 addresses

the data link layer [layer 2] gives the addressing used in sending a frame over local media.

these are called physical addresses.

the addresses are contained in the frame header and specifies the node that the frame is being sent to on the local network.

however, unlike layer 3, layer 2 addresses don't tell what network the device is on.

instead, it just gives it a unique physical address that always stays the same, even on different networks.

because of this, layer 2 addresses are only used to connect devices on the same shared media.

** host to router: the source encapsulates the layer 3 ip packet in a layer 2 frame.

in the frame header, the host adds it's own layer 2 address as the source and the layer 2 address for the recieving router as the destination.

** router to router: the first router [router 1] encapsulates the layer 3 ip packet in a new layer 2 frame.

in the frame header, router 1 adds it's own layer 2 address as the source and the layer 2 address for the second router as the destination.

** router to host: the sending router encapsulates the layer 3 ip packet in a new layer 2 frame.

in the frame header, the router adds it's own layer 2 address as the source and layer 2 address for the host server as the destination.

order of address fields: dest. nic, source nic, source ip, dest. ip

the data link layer is only used for local delivery. layer 2 addresses have no meaning outside the lan.

if it needs to jump to another network, an intermediary device like a router is needed.

layer 3 handles the internetwork buisness.

// 6.3.4 == lan and wan frames

currently, wired lans use ethernet protocols, and wireless lans use wlan protocols.

however, throughout the years, other protocols have been used.

ex: point to point [ppp], high level data link control [hdlc], frame relay, asynchronous transfer mode [atm], x.25.

these above protocols are being replaced in wireless networks by ethernet.

in a tcp/ip network, all of the osi layer 2 protocols work with the ip in osi layer 3.

however, different layer 2 protocols are used based off the local topology and the physical media [where the stuff is and whats connecting it].

to be more specific, the protocol is determined by the technology used to implement the topology.

the technology used depends on the size and services of the network.

all protocols provide media access control [what does what over the media and when].

this allows many different network devices can act as layer 2-operating nodes. thses include nics and switches.

lans typically use high bandwidth technology, but not wans, because it's pricy.

lesson 7: ethernet switching

7.1 == ethernet frames

explains how the ethernet sublayers are related to the frame fields.

// 7.1.1 == ethernet encapsulation

ethernet is one of two lan technologies used today, the other being wlans. ethernet is wired while wlans are wireless.

ethernet operates in the data link layer and the physical layer. ethernet supports from 10 - 10,000 mb[bits]ps.

ethernet is defined by both the data link and physical layer protocols.

// 7.1.2 == data link sublayers

ethernet uses both of the sublayers in the data link layer to operate [llc and mac].

** mac == responsible for data encapsulation and media access control. it also provides data link layer addressing.

** llc == communicates between the networking software at the upper layers and the device hardware at the lower layers.

the llc is in charge of placing information in frames that identifies what layer protocol is being used for the frame.

this lets layer 3 protocls use the same network interface and media.

// 7.1.3 == mac sublayer

this sublayer is responsible for data encapsulation and media access.

what data does it encapsulate?

** ethernet frames [the internal structure of the ethernet frame]

** ethernet addressing [the frame that includes both a source and destination mac address to send the frame from

ethernet nic to ethernet nic on the same lan]

** ethernet error detection [the frame check sequence [fcs] in the trailer]

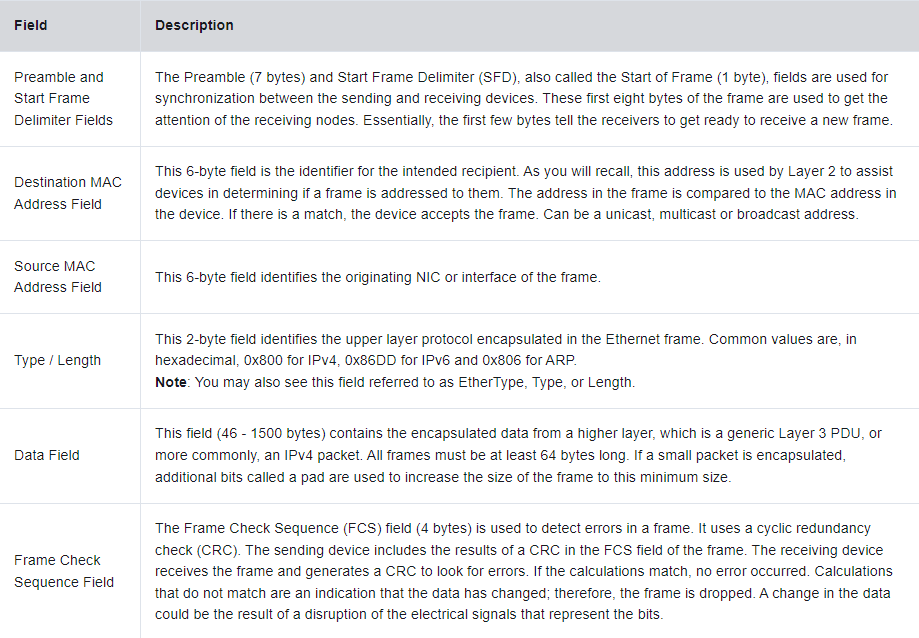

// 7.1.4 == ethernet frame fields

an ethernet frame can be anywhere from 64 bytes to 1518 bytes. this includes all bytes from the destination mac to the fcs trailer. the preamble is not included.

any frame less than 64 bytes is considered a collision fragment or runt frame, and is automatically gotten rid of.

any frame more than 1518 bytes is considered a jumbo frame.

both of these types of frames are dropped by the recieving device.

ethernet frame field details

| field | size |

|---|---|

| preamble and sfd | 8 bytes [not included in total] |

| destination mac address | 6 bytes |

| source mac address | 6 bytes |

| type / length | 2 bytes |

| data | 46 to 1500 bytes |

| fcs | 4 bytes |

7.2 == ethernet mac access

describes the ethernet mac address.

// 7.2.1 == mac address and hexidecimal

quick reminder: ipv4 is represented by binary, while ipv6 and ethernet are represented by hexidecimal.

for a reminder about decimal and hexidecimal, click here.

// 7.2.3 == frame processing

sometimes, mac addresses are reffered to as burned-in addresses [bia] because the address is encoded permanently into the rom on the nic.

note-- on modern nics, this is possible to change and is not permanent.

when a computer boots, the nic copies it's mac address from the rom to the ram.

when this device forwards a message to an ethernet network, the ethernet header includes the source and destination nics.

when a nic recieves an ethernet frame, it checks to see if the destination mac address in the frame matches with the one in the ram of the nic.

if it doesn't match, the frame is discarded, as it means that there is corruption of some kind.

// 7.2.4 == unicast mac address

in ethernet, different mac addresses are used for layer 2 unicast, broadcast, and multicast. quick refresher.

a unicast mac address is the address that is used when a frame is being sent from one device to another single device.

address resolution protocol [arp] is a process used by the source host to determine the destination mac address of the end device.

neighbor discovery [nd] is a process used to determine the destination mac address by seeing what ipv6 addresses are associated with it.

note-- the source mac address must always be a unicast.

// 7.2.5 == broadcast mac address

an ethernet broadcast frame is recieved and held on to by every device on an ethernet lan.

it has many features, including a destination mac address of ff-ff-ff-ff-ff-ff [48 ones],

the ability to flood out all ethernet switch ports except the incoming one,

and the inability to be forwarded by a router.

if encapsulated data is an ipv4 broadcast packet, it means that it's destination ipv4's host section is all ones.

by having this address, it means that all hosts on the local network, or broadcast domain, will get the packet.

// 7.2.6 == multicast mac address

multicast means to send to more than one end device, but not all.

when an ethernet multicast frame is sent, it is only recieved by devices on the ethernet lan in the same multicast group.

when encapsulating a mac address, the destination mac will be 01-00-5e for ipv4 and 33-33 for ipv6.

these packets are also not forwarded by a router, unless the router is configured to route them.

all devices actually end up reciving these packets, but they are discarded by devices not in the multicast group.

again, the source is always a unicast address.

7.3 == the mac address table

explains how a switch builds it's mac address table and forwrads frames.

// 7.3.1 == switch fundamentals

switches can't just forward every frame to all ports. that's where layer 2 mac addresses come in.

the switch forwards frames based only of of it's layer 2 ethernet mac address, and nothing else from the frame.

the switch looks at it's mac address table to forward each frame to the correct computer.

if that sounds vague, it is! i'll get back into it later.

switches have a weird thing called an entry timer. on default, a switch only holds single entrys in the table for 5 minutes at a time.

when it gets a frame from an address already in the table, the timer is reset.

// 7.3.2 == switch learning and forwarding

switches build their mac address tables by looking at the aource mac addresses of frames recieved.

the switch forwards frames by looking for a match between the frame's destination mac and a mac in the table.

[i'm just shortening mac address to mac for the time being. my fingies hurttt]

the switch checks every frame for new information to learn. if the frame contains a source mac not yet in the table,

it's added to the table along with the incoming port number.

if the mac does exist, the switch takes the information anyway and refreshes the table.

note-- macs that are the same but with different ports are treated as new entrys. the table replaces the old port number with the new.

when sending out frames, the switch looks for a match in it's table for the destination mac.

if the mac is in the table, it will forward it out the specified port. if not, it sends it to all ports but the incoming one.

this is called an unknown unicast.

if the destination mac is a broad or multicast, the frame is sent out all ports but the incoming port.

// 7.3.3 == filtering frames

when switches recieve frames from different devices, it can update it's mac table by peeping the source mac of every frame.

when the table contains the destination mac, it can filter the frame out a single port.

// 7.3.4 == mac address tables on connected switches

a switch can have multiple mac addresses associated with a single port.

the switch treats each source mac from the port as a unique entry.

// 7.4.5 == sending the frame to the default gateway

when a device has an ip address that's on a remote network, the frame can't be sent directly to the destination device.

instead, the frame is sent to the default gateway, the router.

7.4 == switch speeds and forwarding methods

describes switch forwarding methods and port settings available on layer 2 switch ports.

// 7.4.1 == frame forwarding methods on cisco switches

in cisco switches, there are 2 frame forwarding methods.

** store and forward switching: the device recieves the entire frame and computes the crc.

if the crc is fine, the switch forwards it out the correct port.

** cut through switching: the device forwards the frame before it is fully recieved.

the destination address of the frame must at least be read before the frame can be forwarded.

[note-- CRC is a mathmatical formula that uses the number of bits to calculate if the recieved frame has an error.

if the crc is a-okay, the switch looks up the destination address, which determines where the frame goes.]

a plus of store and forward is that it looks for errors before sending the frame off. the switch discards any frames with errors.

// 7.4.2 == cut through switching

in cut through switches, the switch sends the data off as soon as it is recieved, even if it isn't done transmitting.

as soon as it can read the destination mac, off it goes. the switch does not check for errors.

theres 2 types of cut through switching:

** fast forward switching: packets are immediately forwarded to the destination. any error packets are discarded by the nic.

this is the most commen type of cut through switching.

** fragment free switching: the first 64 bytes of the frame are stored before forwarding.

this type is seen as a hybrid between store and forward and fast forward.

it only stores the first 64 bytes because most errors occur in these bytes.

some switches are made to use cut-through until a certain amount of errors are reahced, then automatically switch to store and forward.

when the error rate goes back down, this change is undone.

// 7.4.3 == memory buffering on switches

ethernet switches may use buffering to store frames before forwarding them. it's also used when destination ports are busy.

there are 2 kinds of buffering:

** port based memory: frames are stored in queues linked to certain ports. the frame is only sent when all infront of it have sent.

any delays occur even if their are other open destination ports.

** shared memory: all frames are sent to a common memory buffer shared by all ports and the buffer memory is automatically allocated.

the frames in the buffer are linked to the destination port, letting packets be recieved on one port and sent to another.

// 7.4.4 == duplex and speed settings

the two super basic settings on switches are bandwitdh and duplex. these must match between the switch port and any connected devices.

a refresher on the two duplexes:

full duplex means that both ends can send and recieve at the same time, half duplex means only one end can send at a time.

autonegociation is an option on most ethernet switches and nics, letting two devices negociate the best bandwidth and duplex options.

any communicating devices must both either have autonegociation turned on or off. mismatch can cause collisions.

// 7.4.5 == auto mdix

back in the day, certain connections needed certain cables.

nowadays, auto mdix [automatic medium-dependant interface crossover] automatically detects the type of cable attached to a port and configured the interfaces accordingly.

this setting is enabled by default.

lesson 8: network layer

8.1 == network layer characteristics

// 8.1.1 == the network layer

the network layer, or osi layer 3, lets end devices exchange data across networks. ipv4 and v6 are the primary protocols used in this layer.

other protocols include routing protocols like ospf [open shortest path first] and messaging protocols like icmp [internet control message protocol].

network layers preform the following 4 operations to achieve end-to-end communications.

- addressing end devices: end devices need a unique ip address for identification.

- encapsulation: the network layer encapsulates the protocol data unit [pdu] from the transport layer into a packet.

the process then adds ip header information, such as the ip address of the source and destination device. - routing: the network layer can direct the packets to a destination on another network.

to do this, the packet must be processed by a router.

sometimes, packets need to jump across many routers to achieve the most efficiant path.

each jump is called a 'hop'. - de-encapsulation: when the packet gets to the destination, the host checks the destination ip header to see if it matches

it's own. if so, no errors are present, and the packet is sent to the transport layer.

// 8.1.2 == ip encapsulation

ip [the internet protocol] encapsulates the transport layer segment or any other data by adding an ip header.

the ip takes the transport layer packet's segment header and data and wraps that in a new packet with an added ip header.

all data is encapsulated layer by layer. like an onion

the ip header information stays the same from when the packet leaves to when the packet gets where it's going, except when NAT is involved for ipv4.

//8.1.3 == characteristics of ip

ip was designed to be a simple protocol with no bloat, with only the nessecary functions needed to send a packet from a source to a destination

over interconnected systems of networks.

it was not designed to track or manage the flow of packets. this is preformed primarily by tcp at layer 4.

the basic characteristics of ip...

- connectionless: no connection is made with the destination pre- data packet sending.

- best effort: ip is unreliable because packet delivery is not guarenteed.

- media independant: the operation is independant of the media carrying the daya,

// 8.1.4 == connectionless

ip is connectionless, which means that there is no set end-to-end connection made before the data is sent.

it's like sending someone a letter without telling them first.

// 8.1.5 == best effort

ip cuts down on overhead [amount of non-data data in packets] and connections which is great, but also means packets are not guarenteed to get to point b,

because the ip doesn't establish a connection beforehand, and no data or response is sent back to point a.

// 8.1.6 == media independant

ip is indifferent to the media. it can be sent as electronic signals. optical signals, and radio signals [wireless].

the osi data link layer is in charge of preparing an ip packet for transmission over the communications medium.

this allows ip packets to be delivered over any medium. however, different mediums have different pdu maximums.

this trait is called the maximum transmission unit [MDU]. the data link layer tells the network layer the mdu,

and the network layer then decides how big the packet can be.

sometimes, an intermediary device like a router has to split up ipv4 [ipv6 can't be split] packets when sending it to another medium.

this is called fragmentation. fragmentation causes latency [delay].

8.2 == ipv4 packet

// 8.2.1 == ipv4 packet header

headers are needed in these packets to make sure it gets to it's destination or next step to it's destination.

an ipv4 header consists of fields full of binary that is read by the layer 3 process [ip]

// 8.2.2 == ipv4 packet header fields

the binary in each field identifys the various settings of the packet.

signifigant fields include... [copy-pasted]

- version: a 4 bit binary value set to 0100 to intentify this packet as ipv4.

- diffserv [differentainted services][[ds]]: formally called the tos field, this is an 8 bit field used to determine packet priority.

the first 6 bits are the most impoirtant, and are ds code point [dscp] bits. the last 2 are explicit congestion notification [ecn] bits. - time to live [ttl]: contains an 8 bit binary value that is used to limit the lifeline of a packet. the source sets the initial ttl.

this value is then decreased by one for every router that routes it. if the ttl falls to zero, the packet is discarded, and the router

sends a icmp [internet control message protocol] time exceeded message to the source ip. due to the router changing the ttl, it must also recalculate the header checksum. - protocol: used to identify the next level's protocol. it's 8 bit value indicates the data payload type in the packet,

which lets the nnetwork layer send the data to the corrisponding upper layer protocol. common values include icmp [1], tcp [6], udp [17]. - header checksum: used to detect header corruption.

- source ipv4 address: includes the source ipv4 address as a 32 bit binary string. always a unicast address.

- destination ipv4 address: includes the destination ipv4 address as a 32 bit binary string. always either unicast, multicast, or broadcast.

the two most commonly referred to fields are the source and destination ip addresses. these don't usually change.

the internet header length [ihl], total length, and header checksum are used to intentify and validate said packet.

the remaining fields are used to reorder fragmented packets. ipv4 mainly uses identification, flags, and fragment offset fields.

8.3 == ipv6 packet

// 8.3.1 == limitations of ipv4

ipv6 will eventually replace ipv4, but not right now. ipv4 has lots of issues.

** ipv4 address depletion: ipv4 only has a set number of unique addresses availible, which is approx. 4 billion.

** lack of end-to-end connectivity: network address translation [nat] is opten usd in ipv4 networks.

nat lets multiple devices share a single public ipv4 address. but, because it's shared, the internal netwrk host is hidden.

this is a problem for devices that require end-to-end.

** increased network complexity: nat was only meant as a way to transition from ipv4 to ipv6.

nat can also cause extra latency [delay] and make troubleshooting harder.

// 8.3.2 == ipv6 overview

in the 90s, the ietf began to look for a replacement to ipv4. this led to ipv6.

ipv6 includes the following improvements:

** increased address speed: v6 uses 128 bit addressing unlike v4's 32.

** improved packet handling: v6's header has fewer fields and thus is simpler.

** eliminates the need for nat: nat is not needed due to the amount of public v6 addresses.

this can prevent nat-based problems.

v6 also has approx. 340 undecillion addresses, as opposed to v4's small 4 billion.

// 8.3.3 == ipv4 packet header fields in the ipv6 packet header

a big improvement from v4 to v6 is v6's simple headers.

v4 has a header length of up to 60 bytes [20 octets], with 12 fields [excluding options and padding].

v6, on the other hand, has a header length of up to 120 bytes [40 octets], with up to 8 fields.

// 8.3.4 == ipv6 packet header

ipv6 packet header fields include the following:

- version: contains a 4 bit binary value that is 0110 to identify this as a v6 packet.

- traffic class: an 8 bit field that is equivalent to v4's ds field.

- flow label: a 20 bit field that makes sure all packets with the same flow level get the same type of router handling.

- payload length: a 16 bit field that tells the length of the payload [data portion] of the v6 packet.

this does not include the header length, as it is fixed at 40 bytes. - next header: an 8 bit field equivalent to v4's protocol field.

it indicates the data payload type so the network layer can send it to the correct upper layer protocol. - hop limit: an 8 bit field that replaces v4's ttl field. each hop decreases this value by one, until the packet is discarded.

unlike v4, this does not have a v6 header checksum, because this funtions is preformed at both the lower and upper layers.

this also means that the checksum does not ned to be recalculated every hop. - source ip address: a 128 bit field that identifies the sending host's v6 address.

- destination ip address: a 128 bit field that identifies the recieving host's v6 address.

v6 packets may also have extendtion headers [eh] which provide optional network layer information.

these are optional and fit between the v6 header and the payload. they are used for fragmentation and security, among other things.

routers do not fragment v6 packets, unlike v4.

8.4 == how a host routes

// 8.4.1 == host forwarding decision

both v4 and v6 packets are always created at the source host.

this host has to be able to send this packet to the destination host.

to do this, host end devices make their own routing table.

another role of the network layer is to direct packet inbetween hosts. hosts can send the packets to...

- itself: the host can ping itself by sending a special v4 address of 127.0.0.1 or a v6 address of ::1.

this is called the loopback interface. this is used to test the tcp/ip protocol stack of the host. - local host: this host has to be on the same network as the sending host.

the source and destination hosts share the same network address. - remote host: a destionation host on a remote network.

the source and destination hosts do not share the same network address.

the source end device determines whether the packet is destined for a local or remote host.

the source end device also determines whether the destination ip is on the same network that it itself is on.

the method varies by v4 or v6.

** v4: the source device checks it's subnet mask and v4 address to compare and check to see if they share a network.

** v6: local routers sends the local network addresses [the prefix] to all devices on the network.

many networks have several wired and wireless devices connected together using an intermediary device,

like a lan switch or a wap [wireless access point].

this provides interconnections between local hosts on a local network. they can reach eachother and share data with no additional devices.

any device outside this network is considered a remote host. routers are needed to send packets to remote hosts.

the router connected to the local network is called the default gateway.

// 8.4.2 == default gateway

the default gateway is the network device [ex. router] that routes traffic to other networks.

on a network, the default gateway usually has these 3 features:

** a local ip address in the same range as other hosts on the local network [this is the gateway's address.]

** the ability to bring data into and let data out of the local network

** the ability to route traffic to other networks

traffic can't be forwarded out of the network if there is no default gateway, the default gateway's address is not configured, or the default gateway is down.

// 8.4.3 == a host routes to the default gateway

hosts routing tables typically contain a default gateway.

for ipv4, the host either gets the address for this gateway from dhcp [dynamic host configuration protocol] or manually.

for v6, the router advertises it's address. the address can also be inputted manually.

having a configured default gateway creates a default route in the routing table. this is the route your computer will take to contact a remote network.

// 8.4.4 == host routing tables

for windows, 'route print' or 'netstat -r' can be used in cmd to display the routing table. they do the same thing.

this command displays 3 sections:

** interface list: lists the mac addresses and their assigned interface number of every device [that's network capable] on the host.

** ipv4 route table: lists all known v4 routes, including direct connections, local networks, and local default routes.

** ipv6 route table: see above, but for ipv6.

8.5 == introduction to routing

8.5.1 == router packet forwarding decision

routers also contain routing tables. shocker!!

routers examine the destination ip of any incoming packet and searches it's table to tell where to send it.

the table contains all known network addresses [prefixes] and where to send the packet. these are called route entries or routes.

// 8.5.2 == ip router routing table

the routing table stores three types of route entries:

** directly connected networks: these entries are active router interfaces.

routers consider directly connected routes as interfaces that are configured, activated, and have an ip address.

** remote networks: these entries are connected to other routers.

routers learn about remote networks either via dynamic routing protocols or manual configuration.

** default route: most routers also have default routes, like hosts. this is a last resort.

this is used when theres no good match in the table.

a router can learn about remote networks in 2 ways:

manually, where they are manually entered into the table using static routes,

or dynamically, where they are automatically learned using a dynamic routing protocol.

// 8.5.3 == static routing

static routes are entries that are entered manually.

here's an example: R1(config)# ip route 10.1.1.0 255.255.255.0 108.108.108.108

if the topology changes, since the route is static, it doesn't change and would need to be manually fixed.

static routes are most efficiant for smaller networks where change isn't commonplace.

// 8.5.4 == dynamic routing

a dynamic routing protocol lets routers automatically learn and update their information about remote networks, including default routes.

// 8.5.5 == ipv4 router routing tables

unlike host's tables, there are no column headings indentifying the information in a router's routing table.

// 8.5.6 == introduction to an ipv4 routing table

the 'show ip route' command in priviledged exec mode lets one see the ipv4 routing table.

at the start of each entry is an identifying code used to show the route's type and how it was learned.

common types include:

- L - directly connected local interface ip address

- C - directly connected network

- S - manually entered static route

- O - ospf [open shortest path first]

- D - eigrp [enhanced interior gateway routing protocol

note-- a default route has a network address of all zeros.

lesson 9: address resolution

9.1 == mac and ip

// 9.1.1 == destination on same network

sometimes when a host wants to send a message, it might only know the ip address of the destination, but not the mac. how can we fix this??

first, we must understand ethernet lan addresses: physical and logical.

** the physical address, or mac address, is used for nic to nic communication on the same ethernet network.

** the logical address, or ip address, is used to send the packet from a source device to either a local or remote end device.

layer 2 physical addresses [ex. ethernet mac] are used to send data link frames with an encapsulated ip packet from one nic to another on the same network.

if the destination ip is on the same network, the destination mac address will be that of the destination device.

// 9.1.2 == destination on remote network

when a destination ip is on a remote network, the destination mac will be that of the host's default gateway.

ip addresses of ip packets in a data flow are associated with mac addresses for each step of the way using certain protocols.

for v4, arp [address resolution protocol] is used, and for v6, icmpv6 nd [neighbor discovery] is used.

9.2 == arp

// 9.2.1 == arp overview

as said above, arp stands for address resolution protocol, which is used to connect ipv4 addresses to mac addresses.

each ip device on an ethernet network has a unique ethernet mac address.

when an ethernet layer 2 frame is sent, it contains the destination and source mac addresses.

to send a packet to another host of the same ipv4 network, the host must know both the v4 and mac address of the destination.

ip addresses are a given, but mac addresses must be discovered. this is where arp is used.

arp provides 2 basic functions: matching ipv4 addresses to mac addresses, and maintaining a table of ipv4 to mac address matches.

// 9.2.2 == arp functions

when a packet is send to the data link layer to be encapsulated into an ethernet frame, the sending device looks at a table in it's memory to find the mac address associated with the v4 address.

this table is kept temporarily in ram and is called the arp table or cache.

if the packet's destination v4 is on the same network as the source v4, the device will search it's table for the destination v4 address.

if the destination is on a different network, the device searches the table for the v4 address of the default gateway.

for both of these cases, the device is looking for a v4 address and it's matching mac address.

each row of an arp table connects a v4 address to a mac address. this is called a map, or mapping.

the arp table temporarily caches [saves] the mapping for devices on the local network.

if the device locates the v4 address, the matching mac address is used as the frame's destination mac.

if there is no entry, the device sends an arp request.

// 9.2.3 == arp request

a device sends an arp request when it needs a mac matching a v4 address, and there is no mac in it's table.

arp requests are encapsulated directly inside an ethernet frame with no v4 header. instead, the header's informations looks like the following:

** destination mac: ff-ff-ff-ff-ff-ff, a broadcast address, requiring all nics on the lan to process teh request. greedy!!

** source mac: the mac address of the arp request's sender.

** type: 0x806 is the type field, indicating that it is an arp request and that the frame needs to be send to the arp process.

even though it is a broadcast, only the device on the lan with the matching v4 address will respond.

// 9.2.4 == arp operation - arp reply

the device with the target v4 address will respond with an arp reply.

this is encapsulated in an ethernet frame with the following information:

** destination mac: the mac address of the arp request sender.

** source mac: the mac address of the arp reply sender.

** type: 0x806, the arp message type field.

only the requesting device will receive the reply. after the reply is received, the device will add the v4 and it's matching mac to the table.

if no device responds to the request, the packet is dropped.

like routing tables, entries in arp tables are time stamped.

if the device doesn't get a frame from a device before the timestamp expires, the device's entry is removed from the table.

also like routing tables, static entries can be added, but this is rarely done. static entries do not expire and must be manually removed.

// 9.2.5 == arp role in remote communications

when the destination v4 isn't on the same network as the source v4, the source must send the frame to it's default gateway.

the default gateway is the interface of the local router.

when a source device has a packet with a v4 address of another network, the packet is encapsulated in a frame with the mac address of the router.

the v4 address of the default gateway is stored in the v4 configuration of the hosts.

when the host makes a packet to be sent, it checks to see if the destionation v4 and it's own v4 address are on the same layer 3 network.

if this is false, the source looks in it's arp table for the v4 address of the default gateway.

if no gateway entry exists, it uses the arp process to find the mac address of the default gateway.

// 9.2.6 == removing entries from an arp table

each entry has a cache timer that removes the entry if it hasn't been used for a specified period of time.

for windows, this is commonly between 15 and 15 seconds.

manual removal of entries are also possible using commands. after this happens, the arp request process must happen again to map that device.

// 9.2.7 == arp tables on networking devices

on cisco routers, the show ip arp command is used to display the arp table of the device.

on windows, arp -a is used to achieve the same effect.

// 9.2.8 == arp issues - arp broadcasts and arp spoofing

because it is a broadcast frame, an arp request is gotten and looked at by every device on the sender's network.

in some situations, mostly in large networks, this broadcast can reduce performance for a short period of time.

as soon as the initial arp request is sent and the requesting device gets the mac address it needs, the network will go back to normal.

in some cases, arp can pose a security risk. an evil individual like myself could use arp spoofing to perform an arp poisoning attack.

a poisoning attack is when a device sends an arp request, and an evil individual replys to the request with their own mac address.

this results in the evil individual's mac address being added to the table, and all packets meant for the other device are instead forwarded to them.

9.3 == ipv6 neighbor discovery

// 9.3.2 == ipv6 neighbor discovery messages

neighbor discovery, also called nd or ndp, is used for resolution, route discovery, and redirection for ipv6 addresses using icmpv6.

icmpv6 uses 5 messages to achieve these purposes:

** neighbor solicitation messages [device-device]

** neighbor advertisement messages [device-device]

** router solicitation messages [device-router]

** router advertisement messages [device-router]

** redirect messages

neighbor solicitation and neighbor advertisement messages are used for device to device messaging, such as address resolution [arp for v6].

devices include both host computers and routers.

router solicitation and router advertisement messages are used for device to router messaging.

this is mostly used for dynamic address allocation and stateless address autoconfiguartion [slaac].

// 9.3.3 == ipv6 neighbor discovery - address resolution

like arp for ipv4, v6 devices use nd to find mac addresses from known v6 addresses. this is also called mac address resolution.

neighbor solicitation and neighbor advertisement messages are used for mac address resolution.

neighbor solicitation messages request mac addresses, and neighbor advertisement messages reply with mac addresses.

these messages are sent using special ethernet and v6 multicast addresses.

this lets the nic determine if it's meant for it's device without having to pass it on to the os.

lesson 10: basic router configuration

10.1 == configure initial router settings

// 10.1.1 == basic router configuration steps

when configuring initial settings on a router, the following steps should be performed.

remember to always start with enable then configure terminal!!

note-- exit returns you to the previous configuration.

1. configure the device name.

Router(config)# hostname HOSTNAME-GOES-HERE

2. secure privileged exec mode.

Router(config)# enable secret PASSWORD-GOES-HERE

3. secure user exec mode.

Router(config)# line console 0

Router(config-line)# password PASSWORD-GOES-HERE

Router(config-line)# login

4. secure remote telenet / ssh sccess.

Router(config-line)# line vty 0 4

Router(config-line)# password PASSWORD-GOES-HERE

Router(config-line)# login

Router(config-line)# transport input ssh telnet

5. secure all passwords in the config file.

Router(config-line)# exit

Router(config)# service password-encryption

6. provide legal notification. [i will not be]

Router(config)# banner motd DELIMITER MESSAGE-HERE DELIMITER

7. save the configuration!!!

Router(config)# end

Router# copy running-config startup-config

10.2 == configure interfaces

// 10.2.1 == configure router interfaces

congifuring a router is very easy!!! it just includes the following commands:

Router(config)# interface TYPE-AND-NUMBER-HERE

Router(config-if)# description DESCRIPTION-TEXT-HERE

Router(config-if)# ip address IPV4-ADDRESS-HERE SUBNET-MASK-HERE

Router(config-if)# ipv6 address IPV6-ADDRESS/PREFIX-LENGTH

Router(config-if)# no shutdown

note-- when router interfaces are configured, a message confirming the enabled link should appear.

while the description command is not required, it's useful for troubleshooting by providing information about the network type.

description text is limited to 240 characters.

the no shutdown command activates the interface [almost like powering on the interface].

note 2-- on inter-router connections with no ethernet switch, both connected interfaces must be configured and enabled.

// 10.2.2 == configure router interfaces example

R1> enable

R1# configure terminal

Enter configuration commands, one per line.

End with CNTL/Z.

R1(config)# interface gigabitEthernet 0/0/0

R1(config-if)# description Link to LAN

R1(config-if)# ip address 192.168.10.1 255.255.255.0

R1(config-if)# ipv6 address 2001:db8:acad:10::1/64

R1(config-if)# no shutdown

R1(config-if)# exit

R1(config)#

*Aug 1 01:43:53.435: %LINK-3-UPDOWN: Interface GigabitEthernet0/0/0, changed state to down

*Aug 1 01:43:56.447: %LINK-3-UPDOWN: Interface GigabitEthernet0/0/0, changed state to up

*Aug 1 01:43:57.447: %LINEPROTO-5-UPDOWN: Line protocol on Interface GigabitEthernet0/0/0, changed state to up

R1(config)#

R1(config)#

R1(config)# interface gigabitEthernet 0/0/1

R1(config-if)#/description Link to R2

R1(config-if)# ip address 209.165.200.225 255.255.255.252

R1(config-if)# ipv6 address 2001:db8:feed:224::1/64

R1(config-if)# no shutdown

R1(config-if)# exit

R1(config)#

*Aug 1 01:46:29.170: %LINK-3-UPDOWN: Interface GigabitEthernet0/0/1, changed state to down

*Aug 1 01:46:32.171: %LINK-3-UPDOWN: Interface GigabitEthernet0/0/1, changed state to up

*Aug 1 01:46:33.171: %LINEPROTO-5-UPDOWN: Line protocol on Interface GigabitEthernet0/0/1, changed state to up

R1(config)#

above is an example of what it might look like to configure a router named 'r1'.

// 10.2.3 == verify interface configuration

several commands can be used to verify your interface's configuration, but the most useful is show ip interface brief.

show ipv6 interface brief can also be used.

// 10.2.4 == configuration verification commands

the following commands are the most popular show commands used for interface verification

show ip interface brief and show ipv6interface brief:

displays all interfaces, their ip addresses, and their status.

connected and configured interfaces should display a status and protocol of "up".

anything else would indicate a problem.

show ip route and show ipv6 route:

outputs the contents of the ip routing tables in the ram.

show interfaces:

displays statistics for all interfaces on the device. this will only display the ipv4 addressing information.

show ip interface:

displays ipv4 statistics for all interfaces on a router.

show ipv6 interface:

displays ipv6 statistics for all interfaces on a router.

10.3 == configure the default gateway

// 10.3.1 == default gateway on a host

important background information:

if your lan only has one router, that is your default gateway. if your lan has more than one, you must configure one to be the default gateway.

default gateways are only used when a host wants to send a packet to another network.

a default gateway is not used when one device on a lan wants to send to another device on the same lan.

when sending a packet to a device on another lan, the packet would have the destination address of the device,

but would first forward the packet to it's default gateway. the default gateway then forwards the packet out to the appropriate interface to reach the device.

this also applies to ipv6 networks.

// 10.3.2 == default gateway on a switch

to manage a switch over a lan, it must have a switch virtual interface [svi] configured.

the svi is configured with a unique ipv4 address and subnet mask on the lan.

to access this switch from another network, it must also have a default gateway address configured.

to configure a v4 default gateway on a switch, the ip default-gateway IP-ADDRESS global configuration command is used.

the IP-ADDRESS would be the v4 address of the local router interface connected to the switch.

note-- packets coming from host computers connected to the switch must also have the default gateway address configured on their host computer's os.

lesson 11: ipv4 addressing

11.1 == ipv4 address structure

// 11.1.1 == network and host portions

an ipv4 address is a 32 bit address made up of a network portion and a host portion.

to distinguish the two, you must look at the address first.

the network portion's size isn't really consistant in the address. however, it is the same for all devices on the network.

// 11.1.2 == the subnet mask

the purpose of the subnet mask is to differentiate the network and host portions of the v4 address.

it doesn't actually contain any of the address, it just tells the computer where to look for each section of the address.

it's like a computer's roadmap. every '0' is a section of the network portion, while every '1' is not.

// 11.1.3 == the prefix length

most subnet masks are combinations of the numbers 255 and 0, with periods inbetween.

this can get really annoying really quick. there is a better way!!

it's a method called the prefix length.

it tells you how many bits are set to '1', and is written in slash notation. here's an example.

| subnet mask | 32 bit address | prefix length |

|---|---|---|

| 255.0.0.0 | 11111111.00000000.00000000.00000000 | /8 |

the '/8' would tell the computer that the first 8 bits are the network portion, and that the remaining 26 bits are the host portion.

remember, '1's represent the network portion, and '0's represent the host portion.

// 11.1.4 == determining the network - logical AND

a logical AND is one of three boolean operations, in addition to OR and NOT.

logical AND is the comparison of two bits.

if both bits are 1, then the output is 1. if they are any other combination, the output is 0.

to find the network address, the computer preforms an AND on each bit of the host address and the subnet mask.

the first bit of the host address is ANDed to the first digit of the subnet mask, and so on.

the resulting binary is the network address.

// 11.1.6 == network, host, and broadcast addresses

there are three kinds of ip addresses: network, host, and broadcast addresses.

network addresses are addresses that represent a specific network.

three things determine if a device belongs to this network:

* it has the same subnet mask as the network address.

* it has the same network bits as the network address, as indicated with the sibnet mask.

* it is located on the same broadcast domain as other hosts with the same network address.

a host finds it's network address by ANDing between it's ipv4 address and subnet mask.

host addresses are individual addresses unique to a device on the network.

note that different devices on different networks can have the same host address, since there are only 254.

this portion is indicated by 0s in the subnet mask.

this portion can be any combination of bits but 0000 [a network address] and 1111 [a broadcast].

broadcast addresses an address used to send data to every device on the network [the broadcast domain].

a broadcast address will have all 1s in the host portion.

11.2 == ipv4 unicast, broadcast, and multicast

// 11.2.1 == unicast

unicast means to send a message from one device to one device.

a unicast has the destination ip address of the single receiving device.

source ip addresses can only be unicast addresses.

// 11.2.2 == broadcast

broadcast means to send a message from one device to all devices on the network.

a broadcast has the destination ip address with all 1s in the host portion.

a broadcast packet must be processed by all devices in the broadcast domain.